Two books I bought this month were for research for my MarketWatch column. The Family is a scary expose of a cult-like conservative Christian community that numbers many congressmen and other Washington insiders as members. My column on it is here.

The Federalist is of course a classic. I only needed to consult one of the 80-some papers, but figured this is a good one to have on the shelf.

Bought new books by a couple of thriller writers I like: Rennie Airth-Per my posting on Robert Goddard; Daniel Silva-Gabriel Allon starting to sound a little the same, but still good writing; Christopher Reich-Not as good a writer, but clever ideas. Plus a new writer I want to try, Baltimore resident Daniel Fesperman. Not sure if the Michael Chabon book counts as a thriller, but I've been eyeing it since it came out and finally crumpled and bought it.

Mark Feffer is an acquaintance from my Princeton days. He is primarily a Web designer with an editorial background. His novel is POD and I'm actually enjoying it a lot.

The book an Alice Waters is part of my new interest in food writing, though I'm having trouble getting through Omnivore's Dilemma.

Booklog August 2009

Bought: The Dead of Winter-Rennie Airth; September-Mark Feffer; Family-Jeff Sharlet (research); Alice Waters and Chez Panisse-Thomas McNamee; Rules of Deception-Christopher Reich (bargain); The Secret Servant-Daniel Silva (bargain); The Federalist-Hamilton, Jay, Madison (research); The Amateur Spy-Dan Fesperman; The Yiddish Policemen’s Union-Michael Chabon.

Started: The Family; This Boy’s Life-Tobias Wolff; September-Mark Feffer.

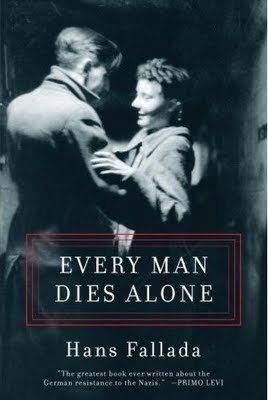

Finished: Every Man Dies Alone-Fallada.

Monday, August 31, 2009

Monday, August 24, 2009

Julia Child

Julie & Julia is a movie about food, about love and about loving food. It is also a film about writing and publishing and the joy of success. I think it works really well, and it's hard to understand some of the reviewers' initial criticisms after seeing the movie.

Meryl Streep is of course great as Julia Child, the American in Paris who truly did change the world with her cookbook. But the other part of the movie, Julie Powell cooking her way through Julia's book and blogging about it, creates about as successful a blend of stories as you can imagine.

For the first time ever, the New York Times reports this morning, Mastering the Art of French Cooking will top the bestseller list next Sunday as a whole new generation of home cooks discovers Julia's masterpiece. This would not have been possible, really, without the role model played by Amy Adams, making this 40-year-old cookbook relevant for today's twenty-somethings. It proves that Julie Powell's effort always was a respectful homage, despite Julia's own criticism, to Julia's original accomplishment.

And Amy Adams, proving herself once again to be the versatile actress she is, holds up her own end, and makes Julie's story, as a personal story, as uplifting as Julia's. Of course, Julie Powell's kitchen in Queens is not likely to find its way to the Smithsonian, and her impact is not of the historic nature as Julia's, but for the purposes of this movie, it turns what could have been a hagiographic biopic into an inspiring human comedy. (Credit is also due to the third genius at work in this film, screenwriter and director Nora Ephron.)

Julie Powell had an extremely clever idea to cook 524 recipes in 365 days and blog about it, and her blog, from what appears of it in the film, was charmingly written with a distinctive voice. Yes, she's riding on Julia's back to success, but Julia herself owes a lot to Larousse Gastronomique and generations of French chefs. The book based on her blog is now out in a new paperback edition with the title, Julie and Julia: My Year of Cooking Dangerously.

The Julia part of the movie is based on My Life in France, a totally charming memoir of the Childs' sojourn in France and Julia's discovery of food and cooking. Dan Burton recommended it to me more than a year ago and it was a true revelation. Aside from the lovely depiction of postwar Paris, the book relates the back story to so many of the recipes in Mastering, adding so much to the appreciation of these descriptions.

Like so many others of my generation, I came to cooking through Mastering. I took up cooking as a hobby when I was living in Hamburg as a way to do something with my hands that was a break from reading and writing all day as a freelancer. Julia's famously foolproof recipes introduced me to so many basic techniques.

Later, in Paris, I was able to go to Cordon Bleu myself -- not for the full program as Julia did, but just a single eight-week class. I took another course later at Anne Willan's Ecole de la Varenne, but always relied on Julia's original book as my touchstone for cooking.

The very revolution that Julia inspired has given us thousands of cookbooks that take all of us into wonderful new ventures in nouvelle cuisine, new American, fusions and all the other exciting stuff that's happening in cooking. Julia's recipes now can seem dowdy and unhealthy. The Times article quotes so many recent purchasers of Mastering as being astonished about the amount of butter and other fat used in the recipes.

That's what's so exciting about Julie Powell's contribution to the movie. She ignored all that and singlemindedly and singlehandedly made Julia relevant again. Now my neighbor is suggesting that we get together with a third couple and cook up a menu from Mastering -- a suggestion I'm sure is being repeated a thousandfold around the country.

I've cooked many of the recipes from Mastering, including the de-boned duck that Julie saved to the end. I've done the carbonnades (beef braised in beer) more often than the boeuf bourguignon featured in the movie, and have repeatedly used her recipes for cassoulet and ratatouille. I may have attempted the aspic early on, but not recently. Living in Europe, I never had the chance to watch French Chef on TV, but the descriptions and drawings in Mastering were generally clear enough to attempt the most ambitious dishes.

Friday, August 21, 2009

Every Man Dies Alone

Hans Fallada can take you from wry irony to terror to a heartbreaking poignancy in the space of a few pages. From the opening chapter's Eva Kluge and her effort to keep her layabout husband out of her apartment to the Gestapo appearing one moment as a the Keystone cops and the next as the loathsome evil they were, the reader is carried along a roller coaster of emotions in this novel about German resistance during the war.

For Fallada, there are good people, and there are bad people. The good people make mistakes and even the bad people are human. But they are bad, irremediably bad. What makes for a good person? At some level, there is integrity, a line that cannot be crossed. Anna Quangel and Trudel Baumann, both good people, crumple under Gestapo torture or are betrayed by their own cowardice, but at some point there is within them a moment when they stand up to the terror. Integrity requires courage, and sooner or later, good people are called upon to display that courage.

Otto Quangel, foreman at a furniture factory that is now making coffins to bury dead troops, breaks with his former disengagement with the world and embarks on the quixotic mission of dropping treasonous postcards in various Berlin buildings. He dreams of his fellow citizens passing these missives furtively among each other, encouraged by this act of resistance to stand fast themselves against the oppressive Nazi regime.

But in fact all but a handful of the postcards are turned into the police by those who find them. These terrorized individuals don't even dare finish reading the cards but turn them in as quickly as possible. Instead of sowing resistance throughout the capital, Quangel is only keeping one Gestapo inspector busy pushing pins into a map of Berlin as each new card narrows his search for his quarry.

When Quangel sees the apparent futility of his resistance, he simply resigns himself to his fate. His fall ensnares all who are close to him, so that his act is beyond futile -- it is fatal for him and those in his life.

But it is a martyrdom that is still better for all concerned than subjection to an evil regime. This is Fallada's message and his condemnation of the German people who failed to resist. They are for him like Enno Kluge -- the cowardly, pathetic shirker who falls victim to the Nazis without ever understanding what happened to him.

Fallada succeeds in creating a novel of ideas without introducing a concept. His characters are everyday people from wartime Berlin, whose motivations are not articulated but speak loudly through their actions. The good people inspire by their hesitant courage, and leave the reader wondering what he or she would do in their place.

Thursday, August 6, 2009

Robert Goddard

It's hard to pin down what I like about Robert Goddard. I picked up Into the Blue as a used book or remainder some years ago, and got around to reading it last year. It's not great literature, but the setting in Greece was appealing, the plot was reasonably intriguing, and the prose was clean and efficient, and sometimes bordering on lyrical.

It was probably the protagonist, Harry Barnett, that kept me reading, though. He is a down-to-earth character, almost a man without qualities, who has lost his way. And he doesn't really find it the course of the novel. But if he is shut down emotionally as the novel begins, he has revived by the time it ends.

This same character, then, appears in Into the Sun, which I read last month on the flight to France. Yes, just sat and read it for five or six hours until I finished it. No Greece this time, and a plot that veered into science fiction. But Harry Barnett kept us on the ground. There was too much coincidence in resolving Harry's dilemma, when he conveniently runs into an old acquaintance to get him out of trouble in Washington. But again, that lean, efficient prose carries you along and Harry's humanity gives you plenty to relate to.

There is something about the language of British writers that is a little grittier than the English Americans use. Rennie Airth is another little known British writer who has a fabulously organic style, an earthy prose the must reach deep into Anglo-Saxon roots.

Airth had an earlier career of writing novels that are all out of print. He has started writing again with a detective who was scarred by World War I solving mysteries in semi-rural England of the 1920s. But these are not your standard English cozies. River of Darkness and Blood-Dimmed Tide are brooding, sometimes brutal, mysteries that explore the darkness of the human spirit, starting with that of the protagonist, John Madden. (Somewhat serendipitously, when I went to check the titles on Amazon, I found that a third John Madden book, The Dead of Winter, was just published July 23, so I ordered it.)

Contrast the muscular prose of a Renee Airth, or even the more workmanlike but still able-bodied language of a Robert Goddard, with that of Alan Furst, an American writer who enjoyed his initial success in England before he became a favorite of the literati here in the U.S.

I started out as a big admirer of Furst, and considered him a role model for my own writing with his atmospheric suspense tales set in Europe between the wars or in the early years of World War II. Furst bravely defied the conventional wisdom that American audiences require an American hero or at least an American setting by featuring European -- continental European, not even British -- protagonists in a purely European setting. He has of course paid the price. While he now has a following in the U.S., he is not likely to break into the bestseller list.

Furst writes in an elegant, elliptical style. He watches old movies from the 30s to glean his sense of atmosphere and translates that brilliantly into prose. His characters are chilly men of the world -- I don't think I've seen a convincing female character in his work -- who arouse little sympathy in the reader. As his novels, each with a title more vague than the last, continued to come out with daunting regularity, I lost my enthusiasm for Furst. Unless you are willing to play his game and cast a youthful Jean Gabin as the protagonist, his books tend to be a little dull.

So I've read The Polish Officer, Kingdom of Shadows, The World at Night, Dark Voyage, and perhaps a couple of others -- I honestly don't remember. I started Foreign Correspondent and Blood of Victory but abandoned both out of boredom. I will probably give them another chance when I'm in a more forgiving mood. The protagonists become indistinguishable from one another and the shadowy plots turn into a big question mark: Who cares?

So I have a couple more Goddard novels on the shelf to read in due course. And I will have the new Rennie Airth by Tuesday. I may break down and get Furst's Spies of Warsaw now that it is in paperback. But I know from experience that if I pick up a Goddard or an Airth I truly will have trouble putting it down, whereas, as the wag quipped, if I put down a Furst novel I have trouble picking it up again.

Labels:

Alan Furst,

Rennie Airth,

Robert Goddard

Tuesday, August 4, 2009

Nordic crime fiction

The runaway international success of Stieg Larsson's The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and its sequels marks what may be the apogee of Nordic crime fiction. It's Raymond Chandler meets Ingmar Bergman as the moody, complex protagonists solve their mysteries in clear, crisp prose. (Ironically, Henning Mankell, creator of Inspector Kurt Wallander, is actually married to Bergman's daughter.)

The international following for these writers started with Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo (a husband and wife team) and their series about Martin Beck in the 60s and 70s. I read a number of those in English while I was living in Europe. One of the novels, The Laughing Policeman, was made into an American film starring Walter Matthau (with the action set in San Francisco and the character called Jacob Martin). Derek Jacobi played Beck in a 1980 international production of The Man Who Went Up in Smoke.

Beck was the quintessential troubled man, who goes through a divorce during the series. He is gloomy about his work -- and who wouldn't be with all the crime and death. The Nordic characters brood about evil and the difficulty flawed police have in fighting it. Beck introduced this atmosphere to the world at large.

Kurt Wallander is Martin Beck's successor. He is actually a little unhappier and a little gloomier than Beck. He drinks and eats junk food as well as any Chandler hero, but he generally muddles through and gets the job done. While Beck operated in Stockholm, Wallander is based in Ystad, in southern Sweden near Malmo, so that Denmark and the Continent are more present in these novels.

Kenneth Branagh is playing Wallander in a BBC series that has appeared on PBS. Branagh brings his customary verve to the role, but he is not really at all as I have imagined the character. Branagh is too energetic, too alert, whereas Wallander often appears almost befuddled, which is an endearing quality.

Hakan Nesser seems to follow the tradition. Inspector Van Veeteren appears in English in Borkmann's Point, which engages like the books of his Swedish predecessors, but does not break any new ground.

It is Stieg Larsson who breaks new ground. His protagonist is a business journalist, not a policeman, who is less cynical about the human condition. But the novels are taken over by the "girl," Lisbeth Salandar, a character of real complexity who takes on astonishing depth in the second novel of the trilogy, The Girl Who Played With Fire. There is mystery, but the Larsson books are as much character-driven as plot-driven. By the second novel, journalist Blomkvist (who mirrors Larsson in real life) fades into the background as Salander grows stronger. The third novel, The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest, will be released in the UK in October of this year.

Larsson, according to Wikipedia, was the world's second-bestselling author last year, after Kite Runner author Khaled Hosseini. Sadly, the Swedish writer died in 2004, leaving behind the manuscripts of the trilogy.

A Swedish miniseries of the trilogy is scheduled for broadcast next year, and Hollywood, again according to Wikipedia, is interested in doing an American version, with the likes of Brad Pitt and Johnny Depp looking to star and Quentin Tarantino or Martin Scorsese to direct.

Larsson seems to owe as much to American and British mystery writers as to his Swedish predecessors, but there is nonetheless a pronounced Nordic element to his novels. Perhaps it is the long winter nights and endless summer days, or the feeling of being on the edge of the world.

I started a book by a Norwegian mystery writer, Jo Nesbro, called Redbreast, but got bogged down and have abandoned it for the time being. The main character seems interesting but we see so little of him in the first part of the book that I lost interest.

Labels:

detective stories,

Henning Mankell,

Stieg Larsson,

Sweden

Saturday, August 1, 2009

Book reading

In our multi-tasking, agenda-driven environment, with its flood of audiovisual entertainment, taking time to sit down and read a book seems almost slothful. Books are read while commuting on trains, on a long flight, or in bed before you turn out the light to sleep.

I don't read enough. I spend all day on the computer and my eyes are tired at night. After dinner, it seems so much simpler to park myself in front of the TV and watch a program, any old program, or something I've recorded, or a new DVD from Netflix, or now some streaming video from Netflix, say a wildly popular British TV series.

We have friends who watch much less TV than we do and they get more books read. I think sometimes film can bring you many of the same rewards that a good book will do, and in such a vivid and stimulating way. But most of what's on television, including those British series, is really just a waste of time.

I do try now to take some time after work and before dinner to sit down and read.

On the weekend, there are errands, dinners, a great outdoors beckoning on a nice day, and it takes some discipline to steal a couple of hours to sit down and read a book.

Who knows, maybe blogging will give me an added incentive to expand that reading time (in short, put reading into my agenda-driven life!).

Netherland

This novel by Joseph O'Neill is not as big a book as its hype makes out, but it's a lovely tale of how human life can be. It is probably not the most profound meditation on the effect of 9/11 in New York, as one blurb has it, and the echoes of Great Gatsby heard by another critic are very faint.

On its own terms, however, Netherland is a wry and poignant love story, a compact and layered slice of life where the novelist effortlessly segues from high finance to pick up cricket.

It is perhaps the passion for cricket that is the freshest element in the book, because who would ever think it could be so much fun. And yet in O'Neill's loving description of the game and what it means to the players, you find yourself as the reader being infected. Washington, like New York, has what appears to be an active amateur cricket league, though I haven't found anyone willing to go watch a game with me.

O'Neill writes in a clean, literate style and is so deft with his characterizations that you see the people and forget you're reading a book. What more can you ask for from a writer?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)